Feature

Echoes of Vauxhall: A Musical Renaissance

Reviving the Sounds of London's Historic Pleasure Gardens

Share this

FIRST PUBLISHED 07 JUL 2024

London has spent many centuries handing over its history to developers, perhaps from the moment King Charles II had to abandon Christopher Wren's magnificent plan for rebuilding after the Great Fire of 1667. It would have cost eight million quid, apparently, which Charles didn't have but could probably have borrowed from Louis XIV across the channel, as he often did. The real reason why London does not have boulevards as splendid as Louis was planning for Versailles that same year, though, is familiar: objections to compulsory purchase. Each landlord of a smouldering pile of cinders in the City demanded that no changes be made to mediaeval ownership rights, and if he insisted, the King could kiss goodbye to his finances. London remained a network of alleys and random buildings, defying the order that Wren's baroque mind wanted to install. He was just left with the churches to build - little bits like St. Paul's Cathedral.

Vauxhall suffered much the same fate a few centuries later. It sits just up river from Westminster but on the other bank of the Thames, opposite the insalubrious Tothill Marshes (which became Pimlico when drained). For 180 years, from before that 1667 fire, Vauxhall was Londoners' favourite destination for a good time with a bit of reasonably respectable culture thrown in, and sometimes some distinctly less than respectable entertainments too. Copenhagen still has somewhere very similar in its Tivoli Gardens, which originally included the name Vauxhall and opened in 1843, just after London's original had gone bankrupt. By then Vauxhall was looking a bit tatty and its fate was sealed when the new railway line smashed across it, extending from Nine Elms station to what became Waterloo. With extra irony, Vauxhall had tried in later years to keep up its appeal by staging re-enactments of the Battle of Waterloo. Having the railway to Nine Elms nearby, and the new Vauxhall Bridge, could have been the moment when easy access made the Pleasure Gardens thrive forever, especially once the Thames was tamed by the embankment.

Instead, a hundred and fifty years later, there is MI6, a bus station, high rise flats for real estate speculators, grim night clubs under railway arches, and a patch of ground which has been given back the name of the Pleasure Gardens since 2012 but without the pavilions, avenues of trees and booths of delights. You will be pushed to find any elms, let alone nine, there either, but there is the new US Embassy. London is always a chancer but heck, it can miss great opportunities too.

All of which explains why the emergence of The Vauxhall Band is a little ray of light along Kennington Lane. When flautist Laura Piras, its artistic director, leads an ensemble from the upstairs room of what used to be the Royal Oak, she is bringing the music back to somewhere that always hosted it. The Royal Oak has now gone Irish and been renamed as Mc & Sons but whatever the name, it was never a stranger to the musicians who played in the pleasure gardens.

Laura will lead a quartet exploring the repertoire that might have been played there in the 18th century, concentrating on the families of flute makers prospering in London at the time. Three sets of craftsmen, Thomas Stanesby and his successor Caleb Gedney in Fleet Street, and the Potter and Urquhart families, supplied the market for the new fashionable transverse, or German, flutes. 'So many survive,' she says, 'that they must have had a ready market.' In the early days they had only one key so that 'some notes produced a slightly veiled sound', considered by composers to be more suitable for pastoral scenes than the more incisive oboe. 'It is not the more homogenous sound you get from later instruments. Sometimes it is nice to go back.' From the middle of the 18th century extra keys started to be added so that by Mozart's time there tended to be six and then eight by the 1790s. However, one-keyed flutes were still played into the early 19th century.

Laura was fascinated with the original flutes in Edinburgh University's collection, held at St. Cecilia's Hall which, built in 1762, is Scotland's oldest purpose-built concert hall (and far older than anything surviving in London, where the Hanover Square Rooms and York Buildings have long since suffered redevelopment). Although she will play on replicas in London, Laura will be playing the original flutes from the museum when the ensemble take the programme from Vauxhall to St. Cecilia's for the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Pubs come to mind there too. After Vauxhall's Mc & Sons, there's Bannerman's Bar opposite St. Cecilia's Hall on Niddry Street for wetting the whistle (whether transverse or not), though sadly the excellent literary retreat of its early days in the 1980s has been replaced by hard rock.

To return to Vauxhall, the great composers of the time were all familiar with the gardens and composed for them. Apart from anything else, this was how a mass audience who could not afford to go to the few licensed London theatres or concert rooms found their music. That in turn spread the word and sold sheet music, although the lack of copyright meant the pirate editions were just as common as the authorised ones. Handel probably had no need of the exposure but it cannot have been unhelpful to Thomas Arne and William Boyce. All three are represented in The Vauxhall Band's programme with trio sonatas. Laura has also chosen music by composers who were well known at the time but have slipped from the limelight since; Carl Weiss and James Oswald, who were also connected with the court of George III, himself a flautist.

There is also a sonata by Lewis Granom, whose family were known as trumpeters as well as flautists - his elder brother John played one in Handel's first opera, Rinaldo, in 1711. By the 1740s Lewis had married a wealthy widow of aristocratic pedigree and mingled in the fashionable society who spent the summers taking the waters in Bath and Tunbridge Wells. He and his brother ran up huge gambling debts but seem to have managed to keep their performing and teaching careers going while lodging in and around the revolting debtors' prisons.

Somehow this constant 18th century mixture of highs and lows, caught so accurately in Hogarth's cautionary cartoons, feels completely in tune with the atmosphere of Vauxhall's pleasure gardens. But, as Laura Piras points out, 'although we hear a lot about the seedy side, there was a big celebrity attendance and they came to hear the best performers in Europe.' One day she would like The Vauxhall Band to play at the same scale as the orchestras that used to perform there but in London now, as then, concerts are so expensive to put on. Sponsors welcome!

The Vauxhall Band performed "The Eighteenth-Century London Flautist" in London and Edinburgh in July and August 2024, supported by a grant from Continuo Foundation.

Author: Simon Mundy

Share this

Keep reading

Les Caractères de l’Amour

Satoko Doi-Luck’s bespoke reconstruction of Mlle Duval’s 1736 opera-ballet receives its UK premiere in a concert performance at Brighton Early Music Festival.

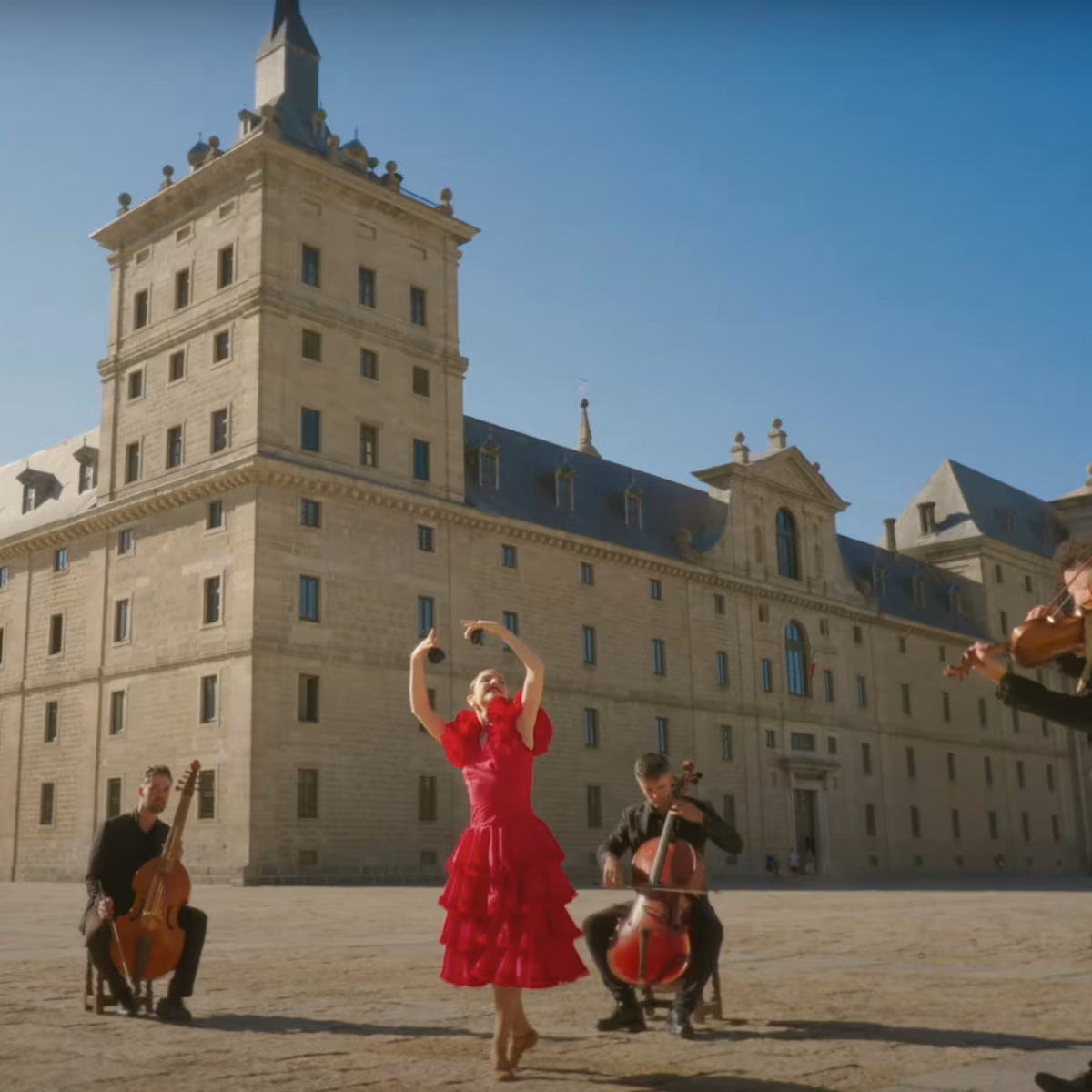

Soler’s Fandango: a new arrangement by the Lowe Ensemble

The Lowe Ensemble performs Antonio Soler's Fandango in an arrangement for strings, harpsichord, baroque guitar, and percussion.

If the Fates allow

On her first solo recital for BIS, Gramophone Award-winner Helen Charlston performs songs by the English composer Henry Purcell and his contemporaries.