Recording

Music for French Kings

A new recording by Baroque in the North

Share this

Baroque in the North's Amanda Babington introduces the group's recent recording, 'Music for French Kings', for Continuo Connect...

An internet search for “musette” will generally yield images of bicycle bags and accordions. Until the 1960s the existence of the bellows-blown French bagpipes of this name had been entirely forgotten. As a result, there are very few recordings of the wealth of repertoire that exists for musette. All the works on this disc are recorded here for the first time, the disc was awarded 4 stars by BBC Music Magazine and was the feature disc of an episode of BBC Radio 3’s Early Music Show on which I was the guest.

My favourite description of the unique sonority of the musette came from Radio 3 presenter Elizabeth Alker who played several excerpts from Music for French Kings on her show before commenting that it reminded her of a favourite Casio keyboard preset! This just goes to show how relatable the instrument is even today. And this is something that we find whenever we use it as part of an event with Baroque In The North, its novelty and sonority attracting audiences from diverse backgrounds.

Baroque In The North is a Manchester-based organisation whose charitable aims are founded on improving accessibility to music. Musicians Claire Babington, David Smith and I share a background in performance and education. And the musette plays a key part in our events, many of which have been kindly supported by Continuo Foundation.

As a recorder player, baroque violinist and musicologist, it is not surprising that my approach to the musette and the interpretation of its repertoire is historically informed, extensive research underpinning my approach to the instrument and its repertoire. In fact, I began learning musette as a hobby but soon found it so fascinating that I ended up studying it first in France and then in Belgium.

“Amanda Babington is an accomplished virtuoso who is exploring [the musette’s] extensive repertoire. The Bourbon dynasty seems to have had a particular liking for the musette and this recording offers a conspectus of the sort of thing they enjoyed.”

— BBC Music Magazine, December 2022

During its short life, the musette’s circumstances, its adoption by royalty, aristocracy and then the bourgeois, prompted composers to write for it and heavily influenced what they composed. Its fast-track adoption was followed by an abrupt fall into obscurity, where it languished until relatively recently. And so there is still much to uncover and understand about the musette and its repertoire.

As with all bagpipes, the musette’s origins are pastoral. A bellows-blown instrument, its closest relatives are the Northumbrian pipes and Uilleann pipes. Its repertoire, however, belongs firmly to the French Baroque canon, its adoption by composers such as Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Jean and Jacques Hotteterre, and Michel Corrette cementing its place in French opera, orchestral and chamber music, with works for both amateur and virtuoso players. And it was the musette’s identity as a Baroque instrument (as opposed to ‘just’ another folk bagpipes) that led first to a failed attempt at revival by Eugène de Bricqueville in 1894, followed by a more successful revival from the 1970s, led initially by flautists Shelley Gruskin and Jean-Christophe Maillard, with contributions from Jean-Claude Compagnon and Sylvette Robson, Remi Dubois and Jean-Pierre van Hees. Both attempts occurred as the result of wider interest in historical performance, and in this sense the musette is a latecomer to the Early Music revival, occurring several decades later than the re-emergence of instruments such as the recorder.

The musette’s position as a high art instrument was cemented almost solely by Louis XIV’s patronage, who used it as part of his ‘peasant’ soirées where he would dress in ‘peasant’ costume (still made from silk, but a little shorter in the hem), enjoy ‘rustic’ music (composed by his finest court composers) and even on occasion be joined by sheep to complete the faux-rustic mis-en-scene. Thanks to Louis XIV’s patronage the musette began to feature in various genres of music, from ballets and operas to duets for two musettes, or musette in combination with another melodic instrument. At the same time, a family of court-based wind players and makers - the Hotteterres - turned their attention towards it.

Given Louis XIV’s affection for the instrument, composers wrote for musette in the hope of securing Royal favour, and interest in the instrument soon spread through the aristocracy, who were always keen to emulate Royal circles. From the 1720s, composers with an eye for commerce, such as Joseph Bodin de Boismortier, saw the opportunity for sales of simple works for amateur musette players. As a result, there was a huge amount and variety of music composed for the instrument over a relatively short period of time, the amount published outstripping that of all other instruments except the violin and the transverse flute. At the same time, famous virtuosi such as Nicolas Chédeville (1705-1782), Colin Charpentier (fl. 1726-1734) and Philibert Delavigne (c.1700-1750) made a fortune performing at the Concert Spirituel and teaching the many students chosen from amongst court circles.

The musette’s decline began as early as the 1750s, against the backdrop of changing society. And the musette’s indelible links to royalty and aristocracy resulted in its total erasure from cultural memory after the French Revolution. However, it is interesting to note that the tradition of labelling as ‘Musette’ movements that include imitations of drones continued. Seen in works by Bach (BWV Anh. 126), Handel (overture to Alcina) and Couperin (Musette de Choisi), compositional ‘Musettes’ continued to appear after the instruments demise in works by composers as diverse as Brahms (Op.24), Grieg (Holberg Suite, piano version), Schoenberg (Op. 25) and Bartok (Out of Doors suite). These echoes were all that was left of the musette until its 20th-century revival.

I was very lucky to work with renowned photographer Paul Husband on the album cover. A true artist, Paul didn’t baulk at my brief which was very vague indeed! I wanted to show the musette as a timeless instrument and so asked him to come up with an image that wasn’t ‘old-fashioned or stuffy’. Our resulting photoshoot at Marple Locks on a windy day caused more than one passing walker to look inquiringly at us and Paul really managed to capture the capricious – perhaps indomitable? - personality of the musette. If you look closely, you can even spot a tiny thistle – a nod to musette’s connections to Scottish royalty as well as the French monarchs!

Want to know more about the tracks on this album? A full version of the liner notes for Music for French Kings is available here!

Music for French Kings is available from Deux-Elles Records and Baroque In The North.

Share this

Keep reading

Reginald Mobley: Countertenor

Internationally acclaimed countertenor Reginald Mobley talks to Continuo Connect about being an artist of colour in early music, his inspirations and passions.

The Spohr Collection Vol. 3

On the latest volume, Ashley Solomon plays on nine original 18th century flutes from Peter Spohr’s private collection.

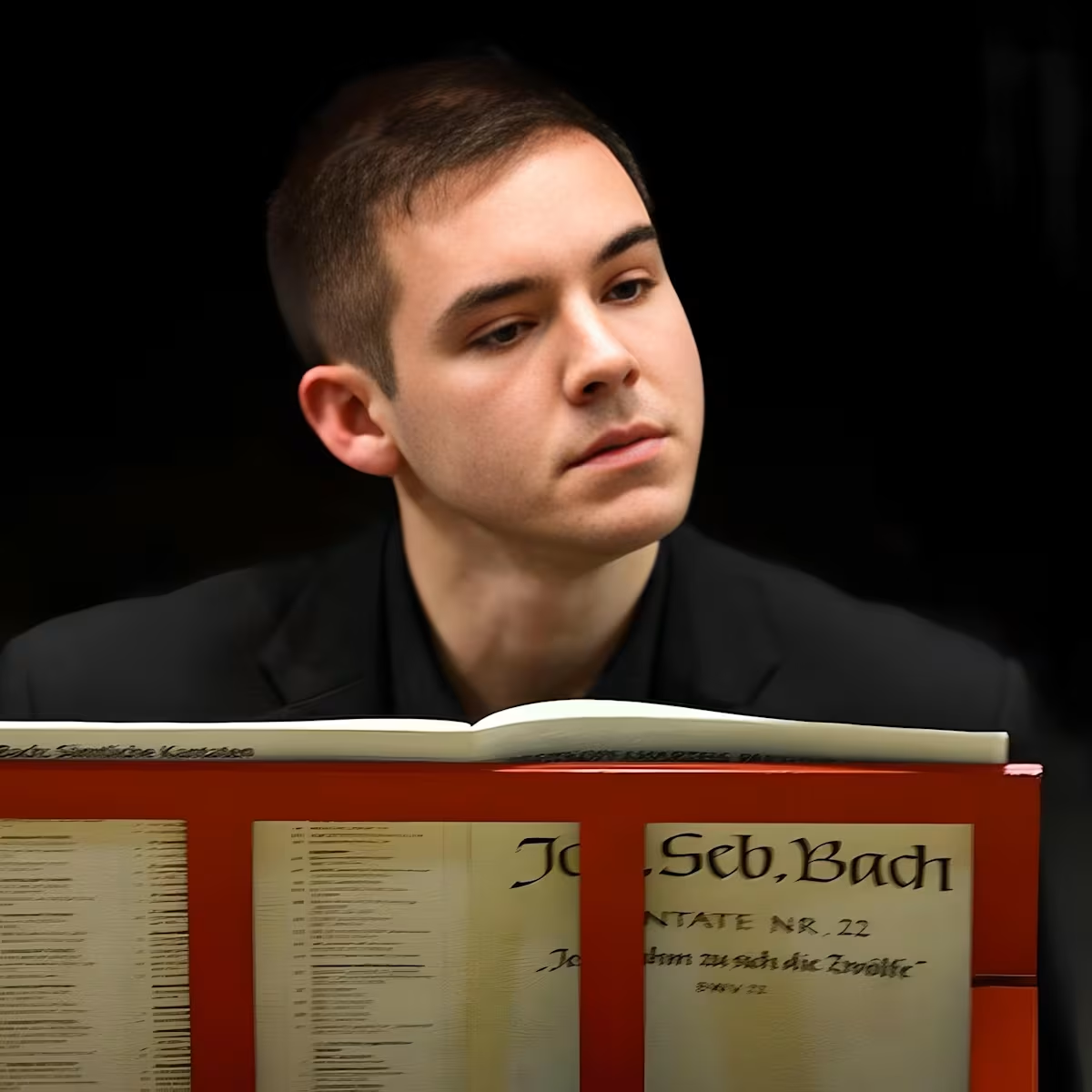

In conversation: Seb Gillot

Seb is a freelance organist, harpsichordist and conductor. He is continually in demand as a continuo player and early keyboard specialist.